Armour-piercing ammunition

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

- Top left: Solid-shot armour-piercing projectiles stuck in armour plate

- Top right: Projectile penetration animation

- Lower left: Perforated 110 mm (4.3 in) armour plate, penetrated by 105 mm (4.1 in) armour-piercing solid-shot projectile

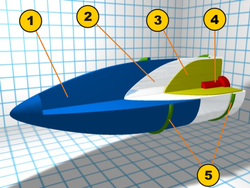

- Lower right: Diagram of capped armour-piercing shell:

• 1. – Ballistic cap or armour-piercing cap

• 2. – Steel alloy kinetic energy penetrator

• 3. – Desensitized high explosive bursting charge

• 4. – Base-fuse (set with delay to explode inside the target)

• 5. – Bourrelet (front) and driving band (rear)

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate armour protection, most often including naval armour, body armour, and vehicle armour.[1]

The first, major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warships and cause damage to their lightly armoured interiors. From the 1920s onwards, armour-piercing weapons were required for anti-tank warfare. AP rounds smaller than 20 mm are intended for lightly armoured targets such as body armour, bulletproof glass, and lightly armoured vehicles.

As tank armour improved during World War II, anti-vehicle rounds began to use a smaller but dense penetrating body within a larger shell, firing at a very-high muzzle velocity. Modern penetrators are long rods of dense material like tungsten or depleted uranium (DU) that further improve the terminal ballistics.

Penetration

[edit]In the context of weaponry, penetration is the ability of a weapon or projectile to pierce into or through an obstacle. It depends on the specific properties of the bullet, the obstacle, and the angle of impact. The speed of the projectile is particularly important, even in the case of the same kinetic energy.[2]

History

[edit]

The late 1850s saw the development of the ironclad warship, which carried wrought iron armour of considerable thickness. This armour was practically immune to both the round cast-iron cannonballs then in use and to the recently developed explosive shell.

The first solution to this problem was effected by Major Sir W. Palliser, who, with the Palliser shot, invented a method of hardening the head of the pointed cast-iron shot.[3] By casting the projectile point downwards and forming the head in an iron mold, the hot metal was suddenly chilled and became intensely hard (resistant to deformation through a Martensite phase transformation), while the remainder of the mold, being formed of sand, allowed the metal to cool slowly and the body of the shot to be made tough[3] (resistant to shattering).

These chilled iron shots proved very effective against wrought iron armour but were not serviceable against compound and steel armour,[3] which was first introduced in the 1880s. A new departure, therefore, had to be made, and forged steel rounds with points hardened by water took the place of the Palliser shot. At first, these forged-steel rounds were made of ordinary carbon steel, but as armour improved in quality, the projectiles followed suit.[3]

During the 1890s and subsequently, cemented steel armour became commonplace, initially only on the thicker armour of warships. To combat this, the projectile was formed of steel—forged or cast—containing both nickel and chromium. Another change was the introduction of a soft metal cap over the point of the shell – so called "Makarov tips" invented by Russian admiral Stepan Makarov. This "cap" increased penetration by cushioning some of the impact shock and preventing the armour-piercing point from being damaged before it struck the armour face, or the body of the shell from shattering. It could also help penetration from an oblique angle by keeping the point from deflecting away from the armour face.

World War I

[edit]Shot and shell used before and during World War I were generally cast from special chromium steel that was melted in pots. They were forged into shape afterward and then thoroughly annealed, the core bored at the rear and the exterior turned up in a lathe.[3] The projectiles were finished in a similar manner to others described above. The final, or tempering treatment, which gave the required hardness/toughness profile (differential hardening) to the projectile body, was a closely guarded secret.[3]

The rear cavity of these projectiles was capable of receiving a small bursting charge of about 2% of the weight of the complete projectile; when this is used, the projectile is called a shell, not a shot. The high-explosive filling of the shell, whether fuzed or unfuzed, had a tendency to explode on striking armour in excess of its ability to perforate.[3]

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, projectiles used highly alloyed steels containing nickel-chromium-molybdenum, although in Germany, this had to be changed to a silicon-manganese-chromium-based alloy when those grades became scarce. The latter alloy, although able to be hardened to the same level, was more brittle and had a tendency to shatter on striking highly sloped armour. The shattered shot lowered penetration, or resulted in total penetration failure; for armour-piercing high-explosive (APHE) projectiles, this could result in premature detonation of the high-explosive filling. Advanced and precise methods of differentially hardening a projectile were developed during this period, especially by the German armament industry. The resulting projectiles change gradually from high hardness (low toughness) at the head to high toughness (low hardness) at the rear and were much less likely to fail on impact.

APHE shells for tank guns, although used by most forces of this period, were not used by the British. The only British APHE projectile for tank use in this period was the Shell AP, Mk1 for the 2 pdr anti-tank gun and this was dropped as it was found that the fuze tended to separate from the body during penetration. Even when the fuze did not separate and the system functioned correctly, damage to the interior was little different from the solid shot, and so did not warrant the additional time and cost of producing a shell version. They had been using APHE since the invention of the 1.5% high-explosive Palliser shell in the 1870s and 1880s, and understood the tradeoffs between reliability, damage, percentage of high explosive, and penetration, and deemed reliability and penetration to be most important for tank use. Naval APHE projectiles of this period, being much larger used a bursting charge of about 1–3% of the weight of the complete projectile,[3] but in anti-tank use, the much smaller and higher velocity shells used only about 0.5% e.g. Panzergranate 39 with only 0.2% high-explosive filling. This was due to much higher armour penetration requirements for the size of shell (e.g. over 2.5 times calibre in anti-tank use compared to below 1 times calibre for naval warfare). Therefore, in most APHE shells put to anti-tank use the aim of the bursting charge was to aid the number of fragments produced by the shell after armour penetration, the energy of the fragments coming from the speed of the shell after being fired from a high velocity anti-tank gun, as opposed to its bursting charge. There were some notable exceptions to this, with naval calibre shells put to use as anti-concrete and anti-armour shells, albeit with a much reduced armour penetrating ability. The filling was detonated by a rear-mounted delay fuze. The explosive used in APHE projectiles needs to be highly insensitive to shock to prevent premature detonation. The US forces normally used the explosive Explosive D, otherwise known as ammonium picrate, for this purpose. Other combatant forces of the period used various explosives, suitably desensitized (usually by the use of waxes mixed with the explosive).

Projectile composition and construction

[edit]Cap and ballistic cap

[edit]| Name | Schematic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AP – Armour-piercing |  |

No cap |

| APC – Armour-piercing capped |  |

|

| APBC – Armour-piercing ballistic capped |  |

|

| APCBC – Armour-piercing capped ballistic capped |  |

Cap suffixes (C, BC, CBC) are traditionally only applied to AP, SAP, APHE and SAPHE-type projectiles (see below) configured with caps, for example "APHEBC" (armour-piercing high explosive ballistic capped), though sometimes the HE-suffix on capped APHE and SAPHE projectiles gets omitted (example: APHECBC > APCBC). If fitted with a tracer, a "-T" suffix is added (APC-T).

Penetrator and filling

[edit]| Name | Schematic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AP – Armour-piercing[a] SAP – Semi-armour-piercing[b] |

|

Solid or hollowed steel body

|

| APHE – Armour-piercing high-explosive[c] SAPHE – Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive[d] |

|

Hollowed steel body Explosive charge

|

| APCR – Armour-piercing composite rigid |  |

High-density hard material Deformable metal

|

| APDS – Armour-piercing discarding sabot |  |

Spin-stabilized penetrator

|

| APFSDS – Armour-piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot |  |

Fin-stabilized penetrator

|

Armour-piercing non-solid shells

[edit]An armour-piercing projectile must withstand the shock of punching through armour plating. Projectiles designed for this purpose have a greatly strengthened body with a specially hardened and shaped nose. One common addition to later projectiles is the use of a softer ring or cap of metal on the nose known as a penetrating cap, or armour-piercing cap. This lowers the initial shock of impact to prevent the rigid projectile from shattering, as well as aiding the contact between the target armour and the nose of the penetrator to prevent the projectile from bouncing off in glancing shots. Ideally, these caps have a blunt profile, which led to the use of a further thin aerodynamic cap to improve long-range ballistics. Armour-piercing shells may contain a small explosive charge known as a "bursting charge". Some smaller-calibre armour-piercing shells have an inert filling or an incendiary charge in place of the bursting charge.

APHE/SAPHE

[edit]Armour-piercing high-explosive (APHE) shells are armour-piercing shells containing an explosive filling, which were initially termed "shell", distinguishing them from non-explosive "shot". This was largely a matter of British usage, relating to the 1877 invention of the first of the type, the Palliser shell with 1.5% high explosive (HE). By the start of World War II, armour-piercing shells with bursting charges were sometimes distinguished by the suffix "HE"; APHE was common in anti-tank shells of 75 mm calibre and larger, due to the similarity with the much larger naval armour-piercing shells already in common use. As the war progressed, ordnance design evolved so that the bursting charges in APHE became ever smaller to non-existent, especially in smaller calibre shells, e.g. Panzergranate 39 with only 0.2% high-explosive filling.

The primary projectile types for modern anti-tank warfare are discarding-sabot kinetic energy penetrators, such as APDS. Full-calibre armour-piercing shells are no longer the primary method of conducting anti-tank warfare. They are still in use in artillery above 50 mm calibre, but the tendency is to use semi-armour-piercing high-explosive (SAPHE) shells, which have less anti-armour capability but far greater anti-materiel and anti-personnel effects. These still have ballistic caps, hardened bodies and base fuzes, but tend to have far thinner body material and much higher explosive contents (4–15%).

Common terms (and acronyms) for modern armour-piercing and semi-armour-piercing shells are:

- HEI-BF – High-explosive incendiary (base fuze)

- SAPHE – Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive

- SAPHEI – Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive incendiary

- SAPHEI-T – Semi-armour-piercing high-explosive incendiary tracer

HEAT

[edit]

High-explosive anti-tank (HEAT) shells are a type of shaped charge used to defeat armoured vehicles. They are very efficient at defeating plain steel armour but less so against later composite and reactive armour. The effectiveness of such shells is independent of velocity, and hence the range: it is as effective at 1000 metres as at 100 metres. This is because HEAT shells do not lose penetrating ability over distance. The speed can even be zero in the case where a soldier places a magnetic mine onto a tank's armour plate. A HEAT charge is most effective when detonated at a certain, optimal distance in front of a target and HEAT shells are usually distinguished by a long, thin nose probe protruding in front of the rest of the shell and detonating it at a correct distance, e.g., PIAT bomb. HEAT shells are less effective when spun, as when fired from a rifled gun.

HEAT shells were developed during World War II as a munition made of an explosive shaped charge that uses the Munroe effect to create a very high-velocity particle stream of metal in a state of superplasticity, and used to penetrate solid vehicle armour. HEAT rounds caused a revolution in anti-tank warfare when they were first introduced in the later part of World War II. One infantryman could effectively destroy any extant tank with a handheld weapon, thereby dramatically altering the nature of mobile operations. During World War II, weapons using HEAT warheads were known as having a hollow charge or shaped charge warhead.[4]

Claims for priority of invention are difficult to resolve due to subsequent historic interpretations, secrecy, espionage, and international commercial interest.[5] Shaped-charge warheads were promoted internationally by the Swiss inventor Henry Mohaupt, who exhibited the weapon before World War II. Before 1939, Mohaupt demonstrated his invention to British and French ordnance authorities. During the war, the French communicated the technology to the U.S. Ordnance Department, who then invited Mohaupt to the US, where he worked as a consultant on the bazooka project. By mid-1940, Germany had introduced the first HEAT round to be fired by a gun, the 7.5 cm fired by the Kw.K.37 L/24 of the Panzer IV tank and the Stug III self-propelled gun (7.5 cm Gr.38 Hl/A, later editions B and C). In mid-1941, Germany started producing HEAT rifle grenades, first issued to paratroopers and by 1942 to regular army units. In 1943, the Püppchen, Panzerschreck and Panzerfaust were introduced. The Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck or 'tank terror' gave the German infantryman the ability to destroy any tank on the battlefield from 50 to 150 m with relative ease of use and training, unlike the UK PIAT.

The first British HEAT weapon to be developed and issued was a rifle grenade using a 2+1⁄2-inch (63.5 mm) cup launcher on the end of the barrel; the British No. 68 AT grenade issued to the British army in 1940. By 1943, the PIAT was developed; a combination of a HEAT warhead and a spigot mortar delivery system. While cumbersome, the weapon at last allowed British infantry to engage armour at range; the earlier magnetic hand-mines and grenades required them to approach suicidally close.[6] During World War II, the British referred to the Munroe effect as the cavity effect on explosives.[4]

Armour-piercing solid shots

[edit]Armour-piercing solid shot for cannons may be simple, or composite, solid projectiles but tend to also combine some form of incendiary capability with that of armour-penetration. The incendiary compound is normally contained between the cap and penetrating nose, within a hollow at the rear, or a combination of both. If the projectile also uses a tracer, the rear cavity is often used to house the tracer compound. For larger-calibre projectiles, the tracer may instead be contained within an extension of the rear sealing plug. Common abbreviations for solid (non-composite/hardcore) cannon-fired shot are; AP, AP-T, API and API-T; where "T" stands for "tracer" and "I" for "incendiary". More complex, composite projectiles containing explosives and other ballistic devices tend to be referred to as armour-piercing shells.

AP

[edit]Early WWII-era uncapped armour-piercing (AP) projectiles fired from high-velocity guns were able to penetrate about twice their calibre at close range (100 m). At longer ranges (500–1,000 m), this dropped 1.5–1.1 calibres due to the poor ballistic shape and higher drag of the smaller-diameter early projectiles. In January 1942 a process was developed by Arthur E. Schnell[7] for 20 mm and 37 mm armour piercing rounds to press bar steel under 500 tons of pressure that made more even "flow-lines" on the tapered nose of the projectile, which allowed the shell to follow a more direct nose first path to the armour target. Later in the conflict, APCBC fired at close range (100 m) from large-calibre, high-velocity guns (75–128 mm) were able to penetrate a much greater thickness of armour in relation to their calibre (2.5 times) and also a greater thickness (2–1.75 times) at longer ranges (1,500–2,000 m).

In an effort to gain better aerodynamics, AP rounds were given ballistic caps to reduce drag and improve impact velocities at medium to long range. The hollow ballistic cap would break away when the projectile hit the target. These rounds were classified as armour-piercing ballistic capped (APBC) rounds.

Armour-piercing, capped projectiles had been developed in the early 1900s, and were in service with both the British and German fleets during World War I. The shells generally consisted of a nickel steel body that contained the burster charge and was fitted with a hardened steel nose intended to penetrate heavy armour. Striking a hardened steel plate at high velocity imparted significant force to the projectile and standard armour-piercing shells had a tendency to shatter instead of penetrating, especially at oblique angles, so shell designers added a mild steel cap to the nose of the shells. The more flexible mild steel would deform on impact and reduce the shock transmitted to the projectile body. Shell design varied, with some fitted with hollow caps and others with solid ones.[8]

Since the best-performance penetrating caps were not very aerodynamic, an additional ballistic cap was later fitted to reduce drag. The resulting rounds were classified as armour-piercing capped ballistic capped (APCBC). The hollow ballistic cap gave the rounds a sharper point which reduced drag and broke away on impact.[9]

SAP

[edit]Semi-armour-piercing (SAP) shot is a solid shot made of mild steel (instead of high-carbon steel in AP shot). They act as low-cost ammunition with worse penetration characteristics to contemporary high carbon steel projectiles.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

APCR/HVAP

[edit]Armour-piercing composite rigid (APCR) in British nomenclature, high-velocity armour-piercing (HVAP) in US nomenclature, alternatively called "hard core projectile" (German: Hartkernprojektil) or simply "core projectile" (Swedish: kärnprojektil), is a projectile which has a core of high-density hard material, such as tungsten carbide, surrounded by a full-bore shell of a lighter material (e.g., an aluminium alloy). However, the low sectional density of the APCR resulted in high aerodynamic drag. Tungsten compounds such as tungsten carbide were used in small quantities of inhomogeneous and discarded sabot round, but that element was in short supply in most places. Most APCR projectiles are shaped like the standard APCBC round (although some of the German Pzgr. 40 and some Soviet designs resemble stubby arrows), but the projectile is lighter: up to half the weight of a standard AP round of the same calibre. The lighter weight allows a higher muzzle velocity. The kinetic energy of the round is concentrated in the core and hence on a smaller impact area, improving the penetration of the target armour. To prevent shattering on impact, a shock-buffering cap is placed between the core and the outer ballistic shell as with APC rounds. However, because the round is lighter but still the same overall size it has poorer ballistic qualities, and loses velocity and accuracy at longer ranges. The APCR was superseded by the APDS, which dispensed with the outer light alloy shell once the round had left the barrel. The concept of a heavy, small-diameter penetrator encased in light metal was later employed in small-arms armour-piercing incendiary and HEIAP rounds.

APCNR/APSV

[edit]

Armour-piercing, composite non-rigid (APCNR) in British nomenclature,[e] alternatively called "flange projectile" (Swedish: flänsprojektil) or less commonly "armour-piercing super-velocity", is a sub-calibre projectile used in squeeze bore weapons (also known as "tapered bore" weapons) – weapons featuring a barrel or barrel extension which taperes towards the muzzle – a system known as the Gerlich principle. This projectile design is very similar to the APCR-design - featuring a high-density core within a shell of soft iron or another alloy - but with the addition of soft metal flanges or studs along the outer projectile wall to increase the projectile diameter to a higher caliber. This caliber is the initial full-bore caliber, but the outer shell is deformed as it passes through the taper. Flanges or studs are swaged down in the tapered section so that as it leaves the muzzle the projectile has a smaller overall cross-section.[9] This gives it better flight characteristics with a higher sectional density, and the projectile retains velocity better at longer ranges than an undeformed shell of the same weight. As with the APCR, the kinetic energy of the round is concentrated at the core of impact. The initial velocity of the round is greatly increased by the decrease of barrel cross-sectional area toward the muzzle, resulting in a commensurate increase in velocity of the expanding propellant gases.

The Germans deployed their initial design as a light anti-tank weapon, 2.8 cm schwere Panzerbüchse 41, early in World War II, and followed by the 4.2 cm Pak 41 and 7.5 cm Pak 41. Although HE rounds were also put into service, they weighed only 93 grams and had low effectiveness.[10] The German taper was a fixed part of the barrel.

In contrast, the British used the Littlejohn squeeze-bore adaptor, which could be attached or removed as necessary. The adaptor extended the usefulness of armoured cars and light tanks, which could not be upgraded with any gun larger than the QF 2 pdr. Although a full range of shells and shot could be used, changing an adaptor during a battle is usually impractical.

The APCNR was superseded by the APDS design which was compatible with non-tapered barrels.

APDS

[edit]

An important armour-piercing development was the armour-piercing discarding sabot (APDS). An early version was developed by engineers working for the French Edgar Brandt company, and was fielded in two calibres (75 mm/57 mm for the 75 mm Mle1897/33 anti-tank gun, 37 mm/25 mm for several 37 mm gun types) just before the French-German armistice of 1940.[11] The Edgar Brandt engineers, having been evacuated to the United Kingdom, joined ongoing APDS development efforts there, culminating in significant improvements to the concept and its realization. The APDS projectile type was further developed in the United Kingdom between 1941 and 1944 by L. Permutter and S. W. Coppock, two designers with the Armaments Research Department. In mid-1944 the APDS projectile was first introduced into service for the UK's QF 6-pdr anti-tank gun and later in September 1944 for the QF-17 pdr anti-tank gun.[12] The idea was to use a stronger and denser penetrator material with smaller size and hence less drag, to allow increased impact velocity and armour penetration.

The armour-piercing concept calls for more penetration capability than the target's armour thickness. The penetrator is a pointed mass of high-density material that is designed to retain its shape and carry the maximum possible amount of energy as deeply as possible into the target. Generally, the penetration capability of an armour-piercing round increases with the projectile's kinetic energy, and with concentration of that energy in a small area. Thus, an efficient means of achieving increased penetrating power is increased velocity for the projectile. However, projectile impact against armour at higher velocity causes greater levels of shock. Materials have characteristic maximum levels of shock capacity, beyond which they may shatter, or otherwise disintegrate. At relatively high impact velocities, steel is no longer an adequate material for armour-piercing rounds. Tungsten and tungsten alloys are suitable for use in even higher-velocity armour-piercing rounds, due to their very high shock tolerance and shatter resistance, and to their high melting and boiling temperatures. They also have very high density. Aircraft and tank rounds sometimes use a core of depleted uranium. Depleted-uranium penetrators have the advantage of being pyrophoric and self-sharpening on impact, resulting in intense heat and energy focused on a minimal area of the target's armour. Some rounds also use explosive or incendiary tips to aid in the penetration of thicker armour. High explosive incendiary/armour piercing ammunition combines a tungsten carbide penetrator with an incendiary and explosive tip.

Energy is concentrated by using a reduced-diameter tungsten shot, surrounded by a lightweight outer carrier, the sabot (a French word for a wooden shoe). This combination allows the firing of a smaller diameter (thus lower mass/aerodynamic resistance/penetration resistance) projectile with a larger area of expanding-propellant "push", thus a greater propelling force and resulting kinetic energy. Once outside the barrel, the sabot is stripped off by a combination of centrifugal force and aerodynamic force, giving the shot low drag in flight. For a given calibre, the use of APDS ammunition can effectively double the anti-tank performance of a gun.

APFSDS

[edit]

Armour-piercing fin-stabilized discarding sabot (APFSDS) in English nomenclature, alternatively called "arrow projectile" or "dart projectile" (German: Pfeil-Geschoss, Swedish: pilprojektil, Norwegian: pilprosjektil), is a saboted sub-calibre high-sectional density projectile, typically known as a long rod penetrator (LRP), which has been outfitted with fixed fins at the back end for ballistic-stabilization (so called aerodynamic drag stabilization). The fin-stabilisation allows the APFSDS sub-projectiles to be much longer in relation to its sub-calibre thickness compared to the very similar spin-stabilized ammunition type APDS (armour-piercing discarding sabot). Projectiles using spin-stabilization (longitudinal axis rotation) requires a certain mass-ratio between length and diameter (calibre) for accurate flight, traditionally a length-to-diameter ratio less than 10[citation needed] (more for higher density projectiles).[citation needed] If a spin-stabilized projectile is made too long it will become unstable and tumble during flight. This limits how long APDS sub-projectiles of can be in relation to its sub-calibre, which in turn limits how thin the sub-projectile can be without making the projectile mass too light for sufficient kinetic energy (range and penetration), which in turn limits how aerodynamic the projectile can be (smaller calibre means less air-resistance), thus limiting velocity, etc., etc. To get away from this, APFSDS sub-projectiles instead use aerodynamic drag stabilization (no longitudinal axis rotation), by means of fins attached to the base of the sub-projectile, making it look like a large metal arrow. APFSDS sub-projectiles can thus achieve much higher length-to-diameter ratios than APDS-projectiles, which in turn allows for much higher sub-calibre ratios (smaller sub-calibre to the full-calibre), meaning that APFSDS-projectiles can have an extremely small frontal cross-section to decrease air-resistance, thus increasing velocity, while still having a long body to retain great mass by length, meaning more kinetic energy. Velocity and kinetic energy both dictates how much range and penetration the projectile will have. This long thin shape also has increased sectional density, in turn increasing penetration potential.

Large calibre (105+ mm) APFSDS projectiles are usually fired from smoothbore (unrifled) barrels, as the fin-stabilization negates the need for spin-stabilization through rifling. Basic APFSDS projectiles can traditionally not be fired from rifled guns, as the immense spinning caused by the rifling damages and destroys the fins of the projectile, etc. This can however be solved by the use of "slipping driving bands" on the sabot (driving bands which rotates freely from the sabot). Such ammunition was introduced during the 1970s and 1980s for rifled high-calibre tank guns and similar, such as the Western Royal Ordnance L7 and the Eastern D-10T.[13] However, as such guns have been taken out of service since the early 2000s onwards, rifled APFSDS mainly exist for small- to medium-calibre (under 60 mm) weapon systems, as such mainly fire conventional full-calibre ammunition and thus need rifling.

APFSDS projectiles are usually made from high-density metal alloys, such as tungsten heavy alloys (WHA) or depleted uranium (DU); maraging steel was used for some early Soviet projectiles. DU alloys are cheaper and have better penetration than others, as they are denser and self-sharpening. Uranium is also pyrophoric and may become opportunistically incendiary, especially as the round shears past the armour exposing non-oxidized metal, but both the metal's fragments and dust contaminate the battlefield with toxic hazards. The less toxic WHAs are preferred in most countries except the US and Russia.[citation needed]

Aerial bombs

[edit]Armour-piercing bombs dropped by aircraft were used during World War II against capital and other armoured ships. Among the bombs used by the Imperial Japanese Navy in the attack on Pearl Harbor were 800 kg (1,800 lb) armour-piercing bombs, modified from 41-centimeter (16.1 in) naval shells,[14] which succeeded in sinking the battleship USS Arizona.[15] The Luftwaffe's PC 1400 armour-piercing bomb and the derived Fritz X precision-guided bomb were able to penetrate 130 mm (5.1 in) of armour.[16] The Luftwaffe also developed a series of bombs propelled by rockets to assist in penetrating the armour of ships and similar targets.[17]

Small arms

[edit]Armour-piercing rifle and pistol cartridges are usually built around a penetrator of hardened steel, tungsten, or tungsten carbide, and such cartridges are often called "hard-core bullets". Rifle armour-piercing ammunition generally carries its hardened penetrator within a copper or cupronickel jacket, similar to the jacket which would surround lead in a conventional projectile. Upon impact on a hard target, the copper case is destroyed, but the penetrator continues its motion and penetrates the target. Armour-piercing ammunition for pistols has also been developed and uses a design similar to the rifle ammunition. Some small ammunition, such as the FN 5.7mm round, is inherently capable of piercing armour, being of a small calibre and very high velocity. The entire projectile is not normally made of the same material as the penetrator because the physical characteristics that make a good penetrator (i.e. extremely tough, hard metal) make the material equally harmful to the barrel of the gun firing the cartridge.[citation needed]

Defense

[edit]Most modern active protection systems (APS) are unlikely to be able to defeat full-calibre AP rounds fired from a large-calibre anti-tank gun, because of the high mass of the shot, its rigidity, short overall length, and thick body. The APS uses fragmentation warheads or projected plates, and both are designed to defeat the two most common anti-armour projectiles in use today: HEAT and kinetic energy penetrator. Defeating HEAT projectiles can occur by damaging or detonating their explosive filling, or by damaging a shaped charge liner or fuzing system. Defeating kinetic energy projectiles can occur by inducing changes in yaw or pitch or by fracturing the rod.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ High-carbon steel solid shot.

- ^ Mild steel solid shot – low-cost ammunition with worse penetration characteristics to contemporary high-carbon steel projectiles.

- ^ Type with a small explosive charge for added post-penetration damage. Designated APHEI if filled with a high explosive incendiary charge.

- ^ Type with a large explosive charge for major post-penetration damage at the cost of penetration. Designated SAPHEI if filled with a high explosive incendiary charge.

- ^ In case of the british Littlejohn adaptor, ammunition was designated as armour-piercing, super-velocity (APSV).

References

[edit]- ^ "Armour-piercing projectile". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ Torecki, Stanisław (1982). 1000 słów o broni i balistyce (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Seton-Karr, Henry (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 864–875.

- ^ a b Bonnier Corporation (February 1945). "The Bazookas Grandfather". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. p. 66.

- ^ Donald R. Kennedy,'History of the Shaped Charge Effect, The First 100 Years – USA – 1983', Defense Technology Support Services Publication, 1983

- ^ Ian Hogg, Grenades and Mortars' Weapons Book #37, 1974, Ballantine Books

- ^ Western Hills Press, Cheviot Ohio Page 3-B May 30th 1968

- ^ Brooks, John (2016). The Battle of Jutland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–79, 90. ISBN 9781107150140.

- ^ a b Popular Science, December 1944, pg 126 illustration at bottom of page on working principle of APCBC type shell

- ^ Shirokorad, A. B. (Широкорад А. Б.) (2002). The God of War of the Third Reich (Бог войны Третьего рейха). M. AST (М.,ООО Издательство АСТ). ISBN 978-5-17-015302-2.

- ^ "Shells and Grenades". Old Town, Hemel Hempstead: The Museum of Technology. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ Jason Rahman (February 2008). "The 17-Pounder". Avalanche Press. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-23.

- ^ Ogorkiewicz, Richard M (1991). Technology of tanks. Jane's Information Group. p. 76.

- ^ Stillwell, Paul (1991). Battleship Arizona: An Illustrated History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 274–276. ISBN 0-87021-023-8. OCLC 2365447.

- ^ Hone, Thomas C. (December 1977), "The Destruction of the Battle Line at Pearl Harbor", Proceedings, vol. 103, no. 12, United States Naval Institute, pp. 56–57

- ^ Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. "Fritz-X", in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 10, p. 1037.

- ^ "Rocket-Propelled Bomb PC 1000 Rs". Catalog Of Enemy Ordnance Material. Office of the Chief of Ordnance. 1 August 1945. p. 316.

Bibliography

[edit]- Okun, Nathan F. (1989). "Face Hardened Armor". Warship International. XXVI (3): 262–284. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Hogg, Ian V. (1985). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ammunition. Apple Press.